Indo-Lanka Fishing dispute : Time for Solutions

The game of arresting and releasing fishermen needs to end. The drama has delayed resolving the problem for far too long. If bilateral agreements have been signed they need to be honored after awareness of clauses that gives entitlements and sovereignty to each signing nation. We have 2 agreements, the 1974 and the 1976 Agreements that have demarcated an International Maritime Boundary Line and has given exclusive rights to each nation. These demarcated areas have been violated, if so by whom, under what conditions and what is the eventual impact is what the solution to the problem should be all about.

India’s demands to release arrested Indian fishermen cannot hide some hard facts:

- Indian fishermen violating IMBL even during LTTE reign have been violating the demarcated IMBL for decades. India was aware and allowed Tamil Nadu fishers to transport arms/ammunition/logistics of medicine and food from Tamil Nadu to LTTE during LTTE defacto rule. Not all but a large number of Tamil Nadu fishermen were part of the LTTE indirect logistics operation. Indian fishermen have been poaching on Sri Lankan waters unchallenged by Sri Lankan fishermen). In 2007 – Maldivian Coast Guard sank Indian trawler (Sri Krishna) which had been transferring ammunition from an LTTE ship. Why did the Indian authorities not make a hue and cry when LTTE ‘arrested Tamil Nadu fishermen and tried them in LTTE kangaroo courts?

- Indian fishers violating bilateral agreements – Indian fishers have violated the 1974/1976 agreement, breached the Exclusive Economic Zone clause, and have been continuously indulging in illegal poaching, stealing fishing profits running into billions of dollars in annual profits. These actions display that India and Tamil Nadu have not been respecting international rules and regulations, international laws and bilateral agreements signed. Taking offence, using media to hype Indian fishermen arrest cannot remove these guilt areas.

- Indian fishers accidentally entering Sri Lankan waters is humbug – Indian fishers and trawlers have GPS systems and are well aware of where they are going. 3000 Indian fleet with GPS straying into Sri Lankan waters cannot be compared to a handful of Sri Lankan fishers with no GPS straying on to Indian waters. The Indians fish 7 days a week as against 2 days by Sri Lankans.

- Indian fishers using internationally banned bottom trawling – Bottom trawling is banned in India after it destroyed Indian side of the IMBL but thousands of them are being used which questions why the Indian Government and the Tamil Nadu state is allowing bottom trawlers to operate knowing that it contributed to destroying India’s marine seabed. Indian bottom trawlers number over 3000 having over 10 landing centres with a crew of 4-5 making up over 10,000 fishermen and over 75,000 dependents (this number will be the bargaining factor for Tamil Nadu politicians)

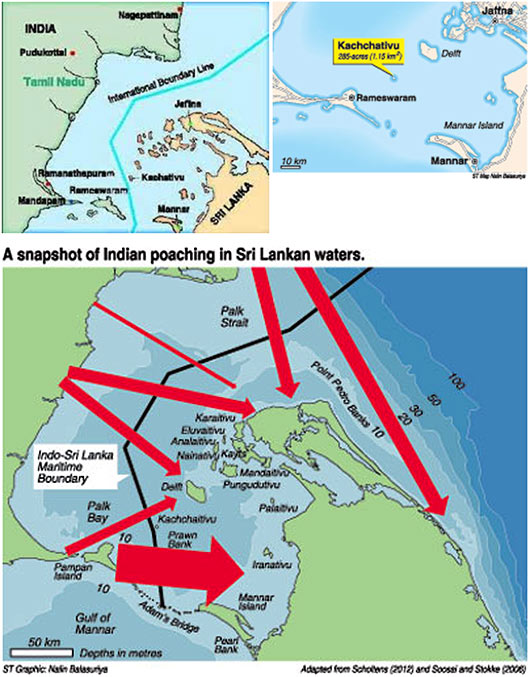

- Indian fishers are poaching on Sri Lankan waters – Sri Lanka’s annual loss as a result of Indian fishers stealing fish that belong to Sri Lanka’s waters is a whopping US$ 750 million annually. The loss has not factored the effects to Sri Lanka’s seabed and other marine life getting destroying with each passing day. Indian trawlers are arriving from Nagapattinam, Thanjavu, Pudukottai, Ramnathapuram and poaching even beyond Kachchativu going as far as Delft, Pesalai, Iranathivu and even upto Pulmoddai (East coast of Sri Lanka) in violation of IMBL.

- Indian fishers ruining Sri Lanka’s side of IMBL by bottom trawling – Sri Lanka’s side of the IMBL has historically had more fish and with the Indian IMBL marine seabed ruined by Indian fishers they are destroying Sri Lanka’s side of the IMBL. Indians don’t care because the destruction of the marine seabed belonging to Sri Lanka is not their headache. Sri Lanka loses USD19.72m from shrimp catch alone. Indian fishers steal 65million kilo grams of fish each year.

- A future of NO FISH – delays in pinpointing where the problem areas are and deciding to solve them is likely to lead to the eventuality that in another 10 years there may be no fish. Livelihoods of fisher folk from both nations will get affected including revenue to the nations.

India’s response to the accusations include:

- Tamil Nadu adopting tactic of victim and projecting itself as the harassed party without acknowledging that Sri Lanka Navy have legitimate rights to arrest Indians poaching on Sri Lankan waters. No poaching – no arrests.

- Tamil Nadu avoiding accountability for violating the IMBL, by putting a political googly in demanding return of Kachchativu, Tamil Nadu attempts to hide the real reason for wanting Kachchativu. Reason for wanting Kachchativu is only to own its fish!

- Tamil Nadu attempts to complicate matters by plugging the Eelam factor into the discussions.

- Indian Central Government did file an affidavit through Deputy Secretary of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Defense in the Madras High Court confirming that no Tamil fishermen had died since 2011 and Sri Lankan Navy was not responsible while also confirming that Sri Lankan boats did not cross the Indian IMBL.

- Bottom line is Indian fishers violating IMBL, poaching on Sri Lankan waters, bottom trawling in thousands and running off with Sri Lanka’s fish as well as ruining the sea bed has nothing whatsoever to do with India’s rights to Kachchativu or Tamil Eelam. Therefore, Indian Premier needs to think twice before allowing himself to be netted into a problem which India is at fault in terms of evidence and facts. Indian Premier should be more concerned about the consequences to 75,000 or more Tamil Nadu families because obviously these fishermen are making a living illegally fishing, therefore India need not wait for the fish to run out, India needs to find alternates if there are no fish on India’s side of IMBL for the Indians to fish because whether with bottom trawlers or not Indian fishers cannot enter Sri Lankan IMBL waters.

International Maritime Boundary and Kachchativu island

Tamil Nadu demand for Kachchativu is ONLY to secure its FISH

A barren uninhabited island about 15miles North-East of Rameshwaran (India) and 14miles South-West of Delft Islands (Sri Lanka). Kachchativu is 3 quarters of a square mile. The minimum distance separating Kachchativu from India is 16km while minimum distance separating Kachchativu and Sri Lanka is 12.8km

Kachchativu came under Sri Lankan jurisdiction because the IMBL boundary fell 1 nautical mile west of Kachchativu. IMBL agreement demarcates sea boundary 18 nautical miles northwest of Point Pedro (in Palk Strait) to Adam’s Bridge (86 nautical miles) Palk Bay extends 70miles – boundaries are on North West by Indian mainland, South to Islands of Rameshwaran and Ramasethu & coral reef known as Adam’s Bridge, East by Lankan coast, North East by a 32mile passage accessing Bay of Bengal known as Palk Strait.

The only structure on the island is the shrine of St. Anthony’s. Kachchativu’s ONLY importance arises from the richness of its seabed a futile ground for prawns, chank shells, pearl oysters and corals. Tamil Nadu demands for Kachchativu is to secure the fertile sea bed that currently Tamil Nadu fishers are poaching upon and political connotations are purely economic.

Sri Lanka made claim to Kachchativu in 1924 on the grounds that Government of India Survey officers treated Kachchativu as part of Ceylon as far back as 1876. Securing Sri Lanka’s case further was Kachchativu Island coming under jurisdiction of Sri Lanka since the Portuguese and even during the British rule, thus the 1924 claim.

The 1974 Agreement was based on these facts. Thus, the historic waters in the Palk Strait & the Palk Bay were demarcated officially endorsing Sri Lanka’s sovereign right to Kachchativu. It is known as the International Maritime Boundary Line (IMBL).

The 1976 Agreement defined maritime boundary for India & Sri Lanka between Gulf of Mannar and Bay of Bengal. The Agreement was signed between India’s foreign secretary and Sri Lanka secretary to the Ministry of Defense and Foreign Affairs, Mr. N. Q. Dias (father of Mr. Gomin Dayasri).

The 1974/76 IMBL agreement denies access to third countries to enter demarcated seas belonging to both India and Sri Lanka respectively.

Article 4 of the Agreement gave sovereign control for both India and Sri Lanka on their side of the demarcated waters/islands/Continental Shelf/sub soil.

Article 5 of the Agreement allocated an Exclusive Economic Zone and gave exclusive jurisdiction over the resources whether living or non-living falling on each side of the border.

Article 5 also gives rights to Indian fishermen without visa to dry nets on Kachchativu and visit the annual St. Anthony’s festival.

Article 5 does not give Indian fishers – fishing rights.

The exchange of letters between Kewal Singh (then Foreign Secretary to GOI) and W T Jayasinghe (then Secretary Ministry of Defence and Foreign Affairs to SL) establishes fishing rights between India and Sri Lanka:

“Fishing vessels and fishermen of India shall not engage in fishing in the historic waters, the territorial sea and the EEZ of Sri Lanka nor shall the fishing vessels and fishermen of Sri Lanka engage in fishing in the historic waters, the territorial sea and the EEZ of India, without the express permission of Sri Lanka or India, as the case may be.”

Therefore, a judgment by court of law in a jurisdiction outside Sri Lanka is not binding on Sri Lanka and cannot alter or impact a bilateral treaty between two sovereign states.

Text of 1974 agreement – http://www.state.gov/documents/organization/61460.pdf

Economic & Social impact to Sri Lanka’s fishers as a result of Indian poachers

- India has been solely benefitting from multibillion dollar shrimp business. India is the largest exporter of shrimps to the EU, Japan and even US. India is said to have over 600 prawn processing plants certified under EU. The shrimps are sourced from Sri Lankan waters. Sri Lanka’s annual loss on shrimps is Rs.4-7billion annually.

- Sri Lanka looses a whopping US$ 750 million annually to Indian poachers.

- 50,000 Sri Lankan fisher families are getting affected because of Indian poaching

- Sri Lankan fishers were denied fishing in view of the strict restrictions during the conflict. With Sri Lankan fishers attempting to resurrect their dormant fishing industry it is unfair for Tamil Nadu, the very state that claims concern for Sri Lanka’s Tamil, should allow Tamil Nadu fishers to intrude into Sri Lankan waters and steal the catch that rightfully belongs to Sri Lankan fishers. Moreover, the method of bottom trawling used would invariably leave Sri Lankan fisher a future of no fish on the Sri Lankan side of IMBL.

Bottom trawlers make humongous noise, use powerful lights and result in destroying Sri Lankan fishermen nets by dragging them with their trawlers

Bottom trawling is illegal in both Tamil Nadu and Sri Lanka, how then can Tamil Nadu fishers operate bottom trawlers which are straying into Sri Lankan waters?

If EU has banned bottom trawling why is the EU importing fish from India sourced from bottom trawling? Should EU strictly insist that India desist from bottom trawling otherwise EU would not import such fish?

Impact of Bottom Trawling

Bottom trawling is also referred as benthic trawling. Bottom trawling is an Illegal, Unregulated and Unreported fishing practice and banned by the Indian Ocean Tuna Committee and the European Union. Indian fishers also indulge in pair trawling (using 2 trawlers working together) which is far dangerous. More than 30% of catch by Indian poachers on Sri Lankan waters are dumped back into the sea as waste fish because it is not commercially viable. For every 1kg of fish there is 20kg of waste fish.

Endangering marine species – coral and plant growth (seagrass) ideal nesting for shrimps, prawns, sea urchins, turtles and Dugongs (marine herbivorous mammals – sea cows).

Scraping bottom of the ocean – muddy and sandy seabed impacted and affects coral and plant growth (which needs a considerable amount of time to regrow)

fishing nets, gear get dragged by the bottom trawlers with

30-40% of what is caught to bottom trawlers get destroyed. Bottom trawlers add poisonous chemicals which are harmful to humans.

Tamil Nadu fishers have destroyed the Indian side of the IMBL by using bottom trawling resulting in few fish. They cannot be allowed to do the same in Sri Lanka’s IMBL.

Global actions against bottom trawling:

- On 17 November 2004, the UN General Assembly urged nations to consider temporary banning bottom trawling.

- In 2006, the UNSG reported that 95% of damage to seamount ecosystems worldwide was due to bottom trawling.

- US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration has banned bottom trawling off its Pacific Coast in 2006.

- The EU closed the Darwin Mounds off Scotland to bottom trawling in 2004,

- In 2005 the FAO’s General Fisheries Commission for the Mediterranean banned bottom trawling and prohibited bottom trawling in Italy, Cyprus and Egypt

- In 1999 Australia prohibited bottom trawling in the South Tasman Sea

Further Reading: National Aquatic Resources Agency (NARA), Marine Biological Resources Division

- http://www.nation.lk/edition/feature-viewpoint/item/ 25716-indian-bottom-trawling-destroys-marine-ecosystem.html #sthash.HhQpdnLm.dpuf

- http://www.nation.lk/edition/feature-viewpoint/item/ 25716-indian-bottom-trawling-destroys-marine-ecosystem.html #sthash.HhQpdnLm.dpuf

- http://www.nation.lk/edition/feature-viewpoint/item/ 25716-indian-bottom-trawling-destroys-marine-ecosystem.html #sthash.HhQpdnLm.dpuf

Greenpeace video about the impacts of bottom trawling in the high seas (a must watch)

Discussions towards a solution must factor in

- Bilateral agreements have nothing to do with State Chief Ministers – When 2 sovereign nations sign bilateral agreements the agreements are between the two countries. Therefore, India must remember not to allow Chief Ministers of States to take over and control discussions.

- IMBL violations have nothing to do with demand for Kachchativu as a right of India or Eelam and these should not be included into discussion on fishing issues. The Tamil Nadu demand for Kachchativu is because of the fertile fish/prawns in its seabed)

- Indian fishers violating 1974/76 Agreement on Sri Lanka’s Exclusive Economic Zone legally denying Indian fishers to enter Sri Lankan waters and Sri Lankan fishers to enter Indian waters.

- Both nations to come to terms with:

- Accepting IMBL boundaries demarcating areas for Sri Lanka and India

- Deciding how to handle violations and violators

- Deciding how to stop illegal poaching violating IMBL boundaries

- Deciding to strictly implement the ban on illegal bottom trawling in view of environmental impact to marine ecosystem

- Security concern of Sri Lanka – given that India had known and did nothing about Indian fishers assisting LTTE to transport arms/ammunition/food & medicines and other logistics, the possibilities of these fishers being used again cannot be ruled out. In making reference to Sri Lanka Navy shooting and killing Indian ‘fishermen’ the fact that this shooting is attributed to their colluding with LTTE should not be overlooked.

- No propaganda lies: Media has been projecting the picture that only Tamil Nadu fishermen are getting arrested and tortured and kept in Sri Lankan prisons whilst never highlighting the treatment of Sri Lankan fishers even though their numbers are far fewer. During 1993-1997 India kept 269 Sri Lankan boats and detained 338 Sri Lankan fishermen. India took 1 year to release them and took several years to release their boats. Unfortunately, Sri Lankan authorities have not been demanding the release of these fishermen as vigorously as the Indian authorities. In fact, the Northern Province Chief Minister claiming to be the voice of the Sri Lankan Tamils is asking for the release of Indian fishermen and not his own people!

- Alternate livelihood for Tamil Nadu fishers: If there are few fish in India’s IMBL, and if IMBL is properly implemented and Indian fishers cannot stray into Sri Lanka’s waters, it means Indian fishers will have to think of an alternate means of livelihood. The Indian Government and Tamil Nadu must work out a separate plan in view of this for the IMBL agreement cannot be compromised to accommodate Indian fishers to Sri Lanka’s side under whatever terms or goodwill gestures even UNHRC support.

- Tamil Nadu or Sri Lankan fishermen cannot decide on territorial issues – meetings between fishers have no legal basis and likely to create further bilateral issues. Fishermen cannot give permission for fishermen of other nations to cross international boundaries.

Where do we go from here?

From the Sri Lankan perspective the issue is the violation of IMBL by Indian fishers, poaching that denies livelihood to Sri Lankan fishers and profits for the nation but most importantly the dangerous likelihood of marine ecosystem getting destroyed and no fish in ten years time.

Whether former discussions covered these areas or not, the fact is that the issues have not been solved. Sri Lanka cannot ignore the above ground realities on the premise that political dealings with India and goodwill matters more.

India cannot be more important than Sri Lanka’s own citizens and Sri Lanka’s own environment.

Sri Lanka’s option’s therefore are:

- Sri Lanka can complain to the EU/Japan and US who purchase shrimps from India and claim that these fish are poached and taken from Sri Lankan waters

- Sri Lanka should consider charging Indian fishers under Article 73 of the UN Convention of the Law of the Sea (not through national laws)

- Sri Lanka can seek assistance of the ICJ – International Court of Jurists who are specialists in solving bilateral disputes.

What is important at this stage is to salvage the gradual destruction caused to the marine ecosystem and marine life. Banning bottom trawling will solve this to a great extent. Next issue is the violation of the IMBL, once India accepts its guilt and commits to ensuring Indian fishers do not stray into Sri Lankan waters, that too can be solved. The solutions look simply enough but why have the delegations from both sides failed? It would be tragic if Sri Lanka’s case is not been defended because of political compromises to India which are never reciprocated no matter how many made.

– by Shenali D Waduge

Latest Headlines in Sri Lanka

- Batalanda commission report tabled in Sri Lankan Parliament March 14, 2025

- Female Grama Niladharis withdraw from night duty over security concerns March 14, 2025

- Sri Lanka ranked as the best country for settling down March 14, 2025

- UN pledges support for Sri Lanka’s industrial and SME development March 13, 2025

- Former Boossa Prison Superintendent shot dead in Akmeemana March 13, 2025