System overhaul needed to stop slide of Sri Lankan cricket

Once a dominant force in world cricket, Sri Lanka’s slide internationally has opened debate in this island nation about whether democracy and a free hand in the administration of the sport is working.

Sri Lankans have long embraced cricket, a colonial legacy, as their own. It’s not only the country’s most popular sport, but also a unifying factor.

This week marked the 25th anniversary of Sri Lankan cricket’s most celebrated achievement — the World Cup triumph in 1996. But the memories of those peaks had fans and critics wondering how it all could have gone downhill so quickly.

Since 2015, Sri Lanka has won just 19 and lost 31 of the 57 test matches it has contested.

Once the pace-setters in the one-day format, Sri Lanka’s record in one-day internationals since 2015 is 33 wins and 64 defeats, including three in a row against the West Indies last week.

In Twenty20s, the quickest and most vibrant from of the game in recent years, Sri Lanka’s record is 19-47.

After winning the World Cup final over Australia in 1996, Sri Lanka has twice been runner-up in the biggest ODI event. It also won the World Twenty20 title in 2014, five years after being runner-up, but hasn’t qualified for the semifinals of any major tournament in the last six years.

Though initial defeats were thought to be temporary in the wake of retirements to some of the biggest stars in the game, the prolonged failure has exposed a system that is no longer producing top-quality players.

Past international players and analysts blame administrators and a lopsided Sri Lanka Cricket constitution and a bloated voting system for stymieing the development of the game domestically.

Democracy “has not worked as far as Sri Lanka Cricket is concerned. There are many loopholes in the constitution which have been exploited by the administration and the clubs,” cricket analysist Callistus Davy said.

Sri Lanka Cricket’s constitution allows for elected officials to simultaneously hold executive positions in clubs at first-class level, increasing the potential for conflicts of interest.

Davy said the government has fired the elected cricket board and installed interim administrations eight times since 1999, citing corruption and mismanagement.

The running of the game has reverted to elections each time, though, because of International Cricket Council regulations which dictate democratic governance of the sport at national level.

Sri Lanka Cricket’s next elections for a two-year term are set for May 20.

Analysts and past players say there are simply too many first-class clubs, which dilutes the talent pool of players but expands opportunities for officials and administrators.

There are 24 clubs playing in first-class competition in Sri Lanka, far higher than the numbers competing in larger countries such as India. Australia, which has a slightly bigger population than Sri Lanka, has six first-class teams in the men’s domestic competition.

More teams also mean more votes. This year, 144 votes cast by regional associations and clubs (comprising four provincial associations, six other cricket associations such as the Defense Services Sports Board and the Sri Lanka University Sports Association, 22 district associations, 28 so-called controlling clubs and 22 affiliated clubs) will decide the office bearers for Sri Lanka Cricket.

Past and current players have for long called for the reduction of clubs to focus more on quality than quantity.

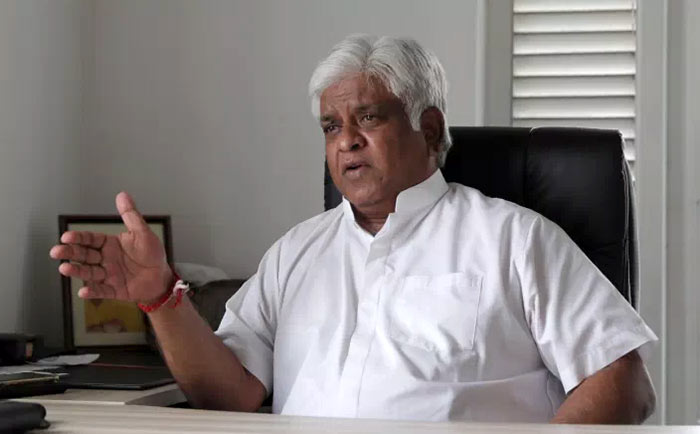

Arjuna Ranatunga, Sri Lanka’s World Cup-winning captain, said the success had brought more money into the domestic game, and that made it more attractive for people to get into the administration of the sport.

“Before we won the World Cup, there was (not much) money involved . . . so many people were hesitant to come into the board,” Ranatunga said. “After ’96, money started coming, that is where all these business people . . . some others with their groups got into cricket.”

Ranatunga said the sports minister needed to intervene again and appoint leaders to govern the sport, and he was confident the ICC would be OK with an interim administration appointed solely for the propose of reforming domestic cricket.

“What has happened to cricket because of democracy? We have already gone down,” he said.

Sri Lanka’s former opening batsman and manager Brendon Kuruppu said officials were preoccupied with local infrastructure at the expense of closing the gap between domestic and international cricket.

“We have too many domestic clubs playing but we have a pool of about 75 players of international quality,” Kuruppu said. “There have been proposals to bring down the clubs down to about 10 (but) it never happens with an elected body because they are looking for votes.”

Muttiah Muralitharan, the all-time leading wicket taker in test cricket, is among the dozen people who’ve sought court intervention to reform cricket governance.

They have petitioned the Court of Appeal to appoint an independent committee to draft a new constitution, and have pointed to other countries where similar moves have worked to improve the strength of the domestic game and the national team.

Sri Lanka Cricket secretary Mohan de Silva rejected suggestions that the board encourages the high number of clubs to maintain voting blocks.

“One cannot say democracy doesn’t help produce players,” he said. He believes the lack of qualities coming through at school level “the cradle of Sri Lanka’s cricket” is having a direct impact at senior level.

De Silva said the board recognized that there was a need to reduce the number of first-class clubs and overhaul the constitution. But, he added, the clubs needed to be encouraged or gently persuaded to take that path because a two-thirds majority is needed to make constitutional reforms.

(AP)

Latest Headlines in Sri Lanka

- Indian PM Narendra Modi to visit Sri Lanka in early April 2025 March 15, 2025

- Sri Lankan President joins special Iftar ceremony at Temple Trees March 15, 2025

- Customs Inspector arrested for smuggling Rs. 30 Million cannabis oil March 15, 2025

- Police constable arrested for taking bribe to issue clearance certificate March 15, 2025

- COPE uncovers irregular NMRA certification process March 14, 2025

The game is already in the cesspool, dear Sir,

The only hope of revival comes from the “Visions of Proserity and Splendor”.